There’s a delicate balance in labbing and studying. During your time spent labbing topic X, your knowledge of topics Y and Z are slowly draining out. When I was studying for the CCIE Security exam, I feel like I spent too much time (about a month straight) working on FLEXVPN. By the time I felt like I had a really good handle on it, I realized I had regressed quite a bit on every other topic. I wasn’t balance in my approach.

This brings me to MPLS. According to the blueprint, MPLS and DMVPN combined make up just 15% of the exam. (MPLS is a huge topic on the CCIE Service Provider exam, spanning multiple sections.) So the trick for the Enterprise Infrastructure lab will be determining how much time and effort I put into learning the nuts and bolts of MPLS. At the moment, my knowledge is about a 1 out of 5. I understand the how and why at a pretty basic level, but I definitely need to sharpen up. So let’s take a look at labminutes.com and see what kind of MPLS offerings they have:

Ouch. First, notice MPLS doesn’t even sit under the R/S section, it’s under Service Provider. And there are 61 videos, averaging 20 minutes each, so probably in the 20 hour ballpark. How far can you afford to go down that rabbit hole? Sadly, the answer is “All the way.” We just have to bite the bullet and learn it all. If we learn it inside and out then it probably will barely show up on the lab. But if we learn it half-assed, then it’ll most likely be a huge chunk right at the center of the exam, and if you can’t get it working everything around it falls apart.

The key is to have a steady labbing schedule where you constantly review the things you’re pretty comfortable with while continuing to dive into things that you suck at.

So let’s get started:

I’m going to rely on three sources:

- As always, LabMinutes – Video: Service Provider | Lab Minutes

- MPLS in the SDN Era –

- MPLS Fundamentals –

Why MPLS?

According to MPLS Fundamentals, it’s no longer about faster switching since the hardware has advanced to a point where there’s no real gain from the faster lookup of 20-bit labels as opposed to full 32-bit routes. So let’s look at the real reasons:

- The use of one unified network infrastructure.

- Better IP over ATM integration.

- Border Gateway Protocol (BGP)-free core.

- The peer-to-peer model for MPLS VPN.

- Optimal traffic flow.

- Traffic engineering.

MPLS Fundamentals breaks all these down in a lot of detail. But for right now, I want to focus on the third one, BGP-free Core.

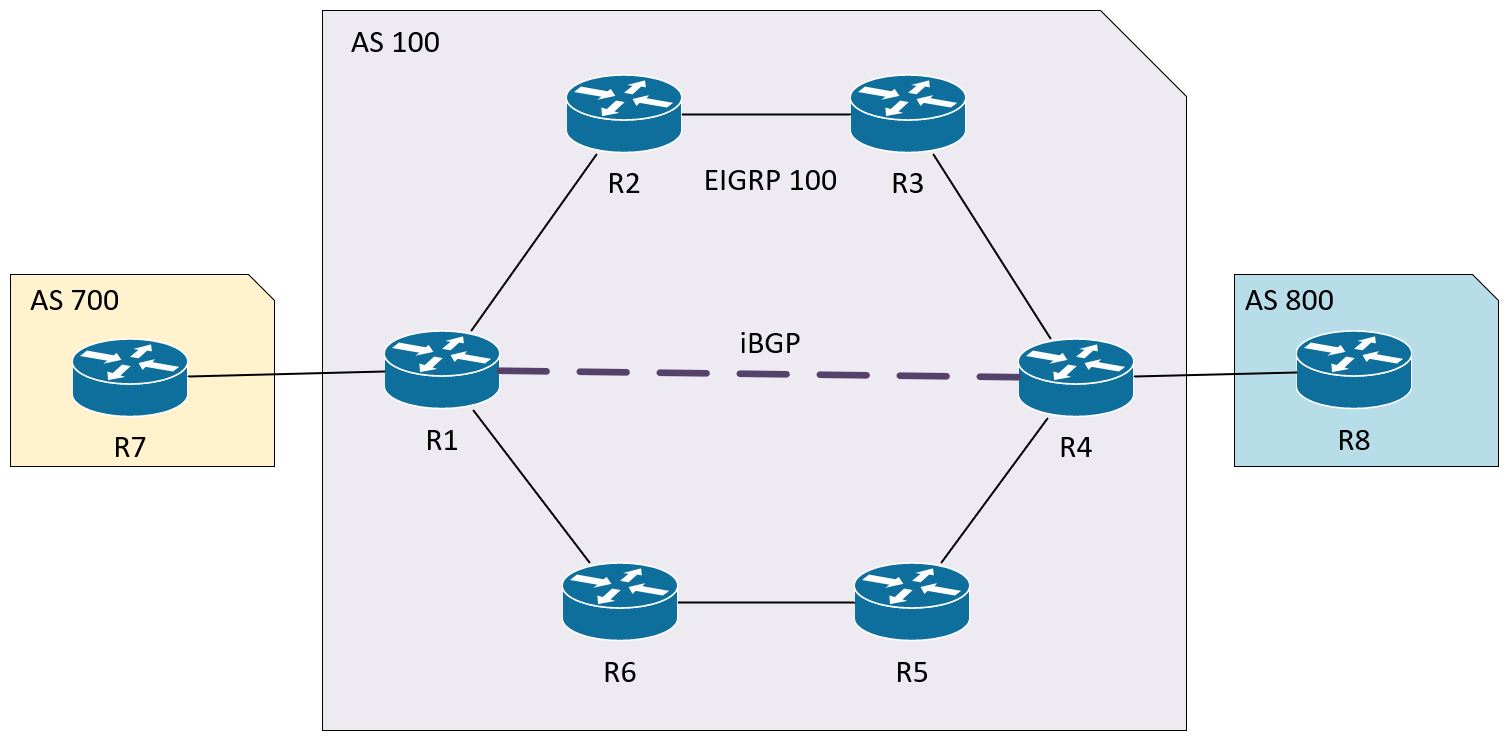

Let’s take a look at the topology we’ll be labbing with:

The idea is that AS 100 is a transit AS between AS 700 and AS 800. There’s no direct link between R1 and R4, there’s just the logical iBGP neighborship. So we have a little bit of a problem here.

We want to get traffic between 10.7.0.1 in AS 700 to 10.8.0.1 in AS 800.

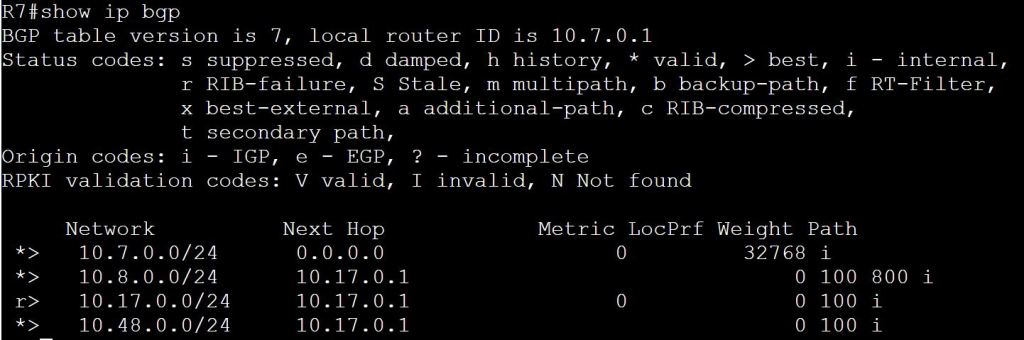

Let’s check R7’s BGP table:

Let’s try a traceroute:

So let’s figure out why this is failing. We’ll start by verifying that R1 knows the way to 10.8.0.1.

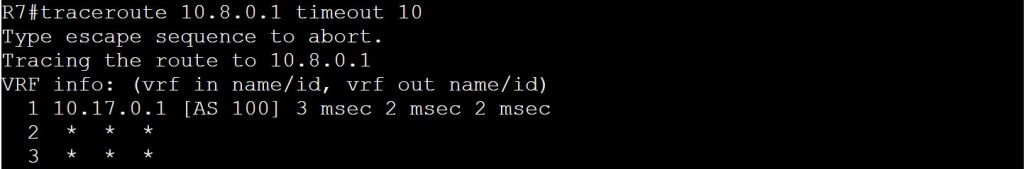

Looks good from R1’s perspective:

R1 learned from BGP to take 10.48.0.8 to get to 10.8.0.1.

To get to 10.48.0.8, take 10.4.4.4, which was also learned through BGP.

To get to 10.4.4.4, take 10.16.0.6 or 10.12.0.2, which R1 learned from EIGRP.

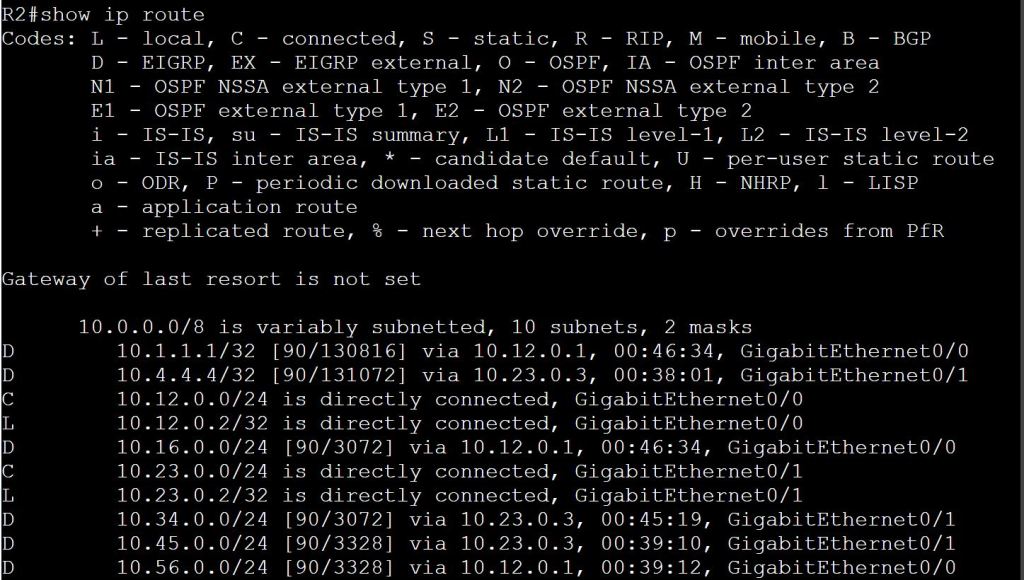

So then let’s check 10.12.0.2:

Looks like R2 has no idea how to get to the 10.8.0.0/24 network, or the 10.7.0.0/24 network.

What we have here is a failure to communicate. What are our options then?

- We could run iBGP on all of the routers in the core of AS 100, but we don’t want to overload all those guys in the middle with these potentially huge routing tables. Plus we’d have to do a full mesh, or set up some route-reflectors.

- We could redistribute our routes between EIGRP and BGP, but of course we don’t want to lose our BGP attributes, so that’s not a good option.

- What about this MPLS business? With MPLS, the EIGRP routers don’t really need to know where 10.8.0.0 and 10.7.0.0 are. They just need to look at their local label and the remote label of the directly connected neighbor. The actual source and destination IPs in that packet don’t matter.

MPLS Configuration

The good news is, the basic configuration is pretty easy and straightforward.

R1:

(Make sure your loopbacks are reachable by your neighbor)

mpls ldp router-id loopback 1

(Configure on the interfaces where your EIGRP 100 neighbors are hanging out.)

interface gig0/1

mpls ip

interface gig 0/2

mpls ip

A note about speed and the ticking of the clock during the exam. The clock is your biggest enemy. On my first attempt at the CCIE Security lab, I felt like if I had about 18 or 24 hours to complete it, I could’ve passed. I felt like I could’ve figured out and configured most of the tasks if I had unlimited time. But that 8-hour clock is killer. After that trouncing, I began to lab for speed. Key changes I made to my game plan were cutting out unnecessary keystrokes and breaking the habit of hitting the tab key. (The other big one was using notepad and copying/pasting configs from there.) Every second counts. So when you’re configuring MPLS on an interface it should be more like this:

R1:

mp ld r loo1

in gi0/0

mp i

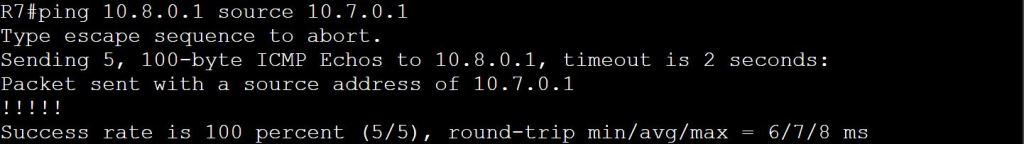

So after slapping on that super-easy config, let’s try a ping:

3.1.a i Label stack, LSR, LSP

For the sake of completeness, I want to just touch on each of the subsections under 3.1.a.

- Label Stack:

- Basically, LSRs (which we’ll learn about in a minute) might need more than one label stacked on top of each other.

- From a packet perspective, they’re in sequence after the L2 header and before the L3 header.

- In short, you can have multiple labels nested (unlike TrustSec cts tags, which is one and only one.)

- You know you got to the bottom of the stack when the BoS bit is set to 1.

- LSR:

- A Label Switching Router. In our diagram, these are R1 through R6.

- Three types exist, but the only difference is which interfaces have MPLS configured.

- Ingress LSR: Gets the unlabeled packet on the way in and applies a label.

- Intermediate LSR: Switches labeled packets in one interface and out the other, swapping out the label each time.

- Egress LSR: Takes the label off and shoots it out the exit interface.

- LSP:

- Label Switching Path.

- Basically the path through the MPLS domain. In our case it would be R1-R2-R3-R4 or R1-R6-R5-R4.

3.1.a ii LDP

You need a method of distributing these labels around your network. The only real options would be modifying routing protocols to carry that burden, or come up with a separate Label Distribution Protocol. MPLS Fundamentals talks a bit about this, but the short answer is that the only routing protocol that really handles label distribution is BGP (which is not an IGP, of course) for MPLS VPN networks. That’s why we need LDP running. The basics of how it works:

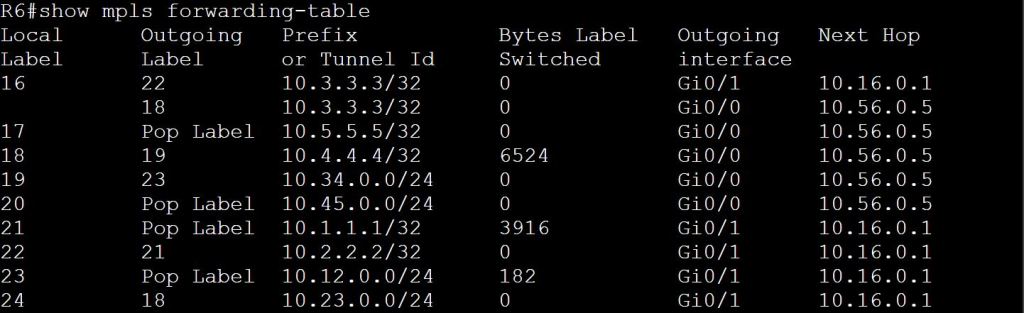

- LSRs distribute the label-to-prefix bindings to their neighbors.

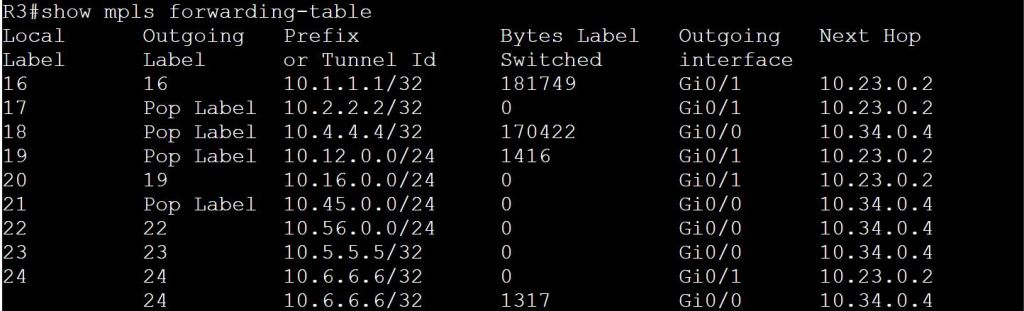

- These received bindings are what we see as “Outgoing Labels” with the show mpls forwarding-table command.

- The LSR has to pick just one remote binding for a prefix. This is done using the regular RIB.

- LFIB is used for the forwarding of the labeled packets.

- The full list of bindings is the LIB. The LFIB is just one of those entries that’s used for forwarding.

3.1.a iii MPLS ping, MPLS traceroute

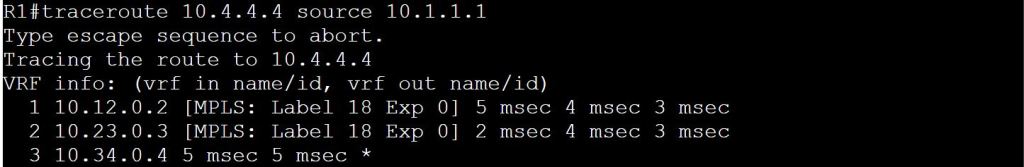

The big takeaway is that MPLS traceroute doesn’t work like regular traceroute. The ingress LSR (R1) sends the ICMP message with the TTL of 1 to the first intermediate LSR (R2), similar to regular traceroute, but from there it’s a totally different story. That first intermediate LSR (R2) buffers out the label stack and sends it all the way to the end of the MPLS domain (R4) with a source IP of his own interface that connects to the ingress LSR (R1) and a destination IP of the ingress LSR (R1). It’s pretty wonky.

For the above screen cap, I had shut down the link to R6 to keeps things simple.

One thing to note, MPLS labels are locally significant. So each LSR can use the same number to mean a different thing. Not that Label 18 shows up twice. This doesn’t mean the label isn’t swapped out. Let’s look at the mpls tables.

For contrast, let’s check the other path that goes through R6 and R5:

One thought on “3.1 MPLS: 3.1.a Operations”